Barkley L. Hendricks: Revolutionizing Black Portraiture in Contemporary Art

Explore the revolutionary work of Barkley L. Hendricks, whose life-sized portraits of Black Americans redefined contemporary portraiture and challenged traditional art historical narratives

I wasn’t a part of any “school.” The association I had with artists in Philadelphia didn’t inspire me in any direction other than my own. I spent my time looking to the Old Masters.

—Barkley L. Hendricks, 2017

The Pioneer Who Put Black Bodies in Old Master Frames

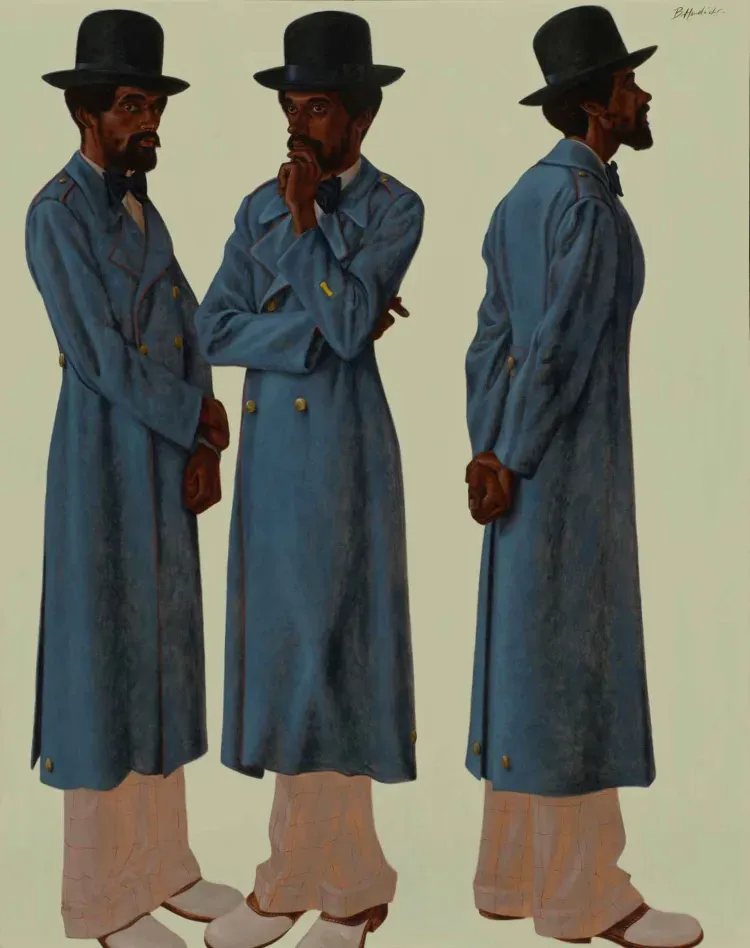

When Barkley L. Hendricks (1945-2017) walked through European museums in the mid-1960s, he was struck by two profound realizations: the masterful technique of portrait painters like Velázquez and van Dyck, and the complete absence of people who looked like him. This transformative experience would shape his entire artistic practice, leading him to create some of the most influential Black portraiture of the 20th century.

Born in North Philadelphia during the Great Migration, Hendricks attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts before earning both BFA and MFA degrees from Yale University. But it was his European travels that crystallized his artistic mission: to paint Black Americans with the same dignity, scale, and technical brilliance traditionally reserved for European aristocracy.

Icons of Defiance and Style

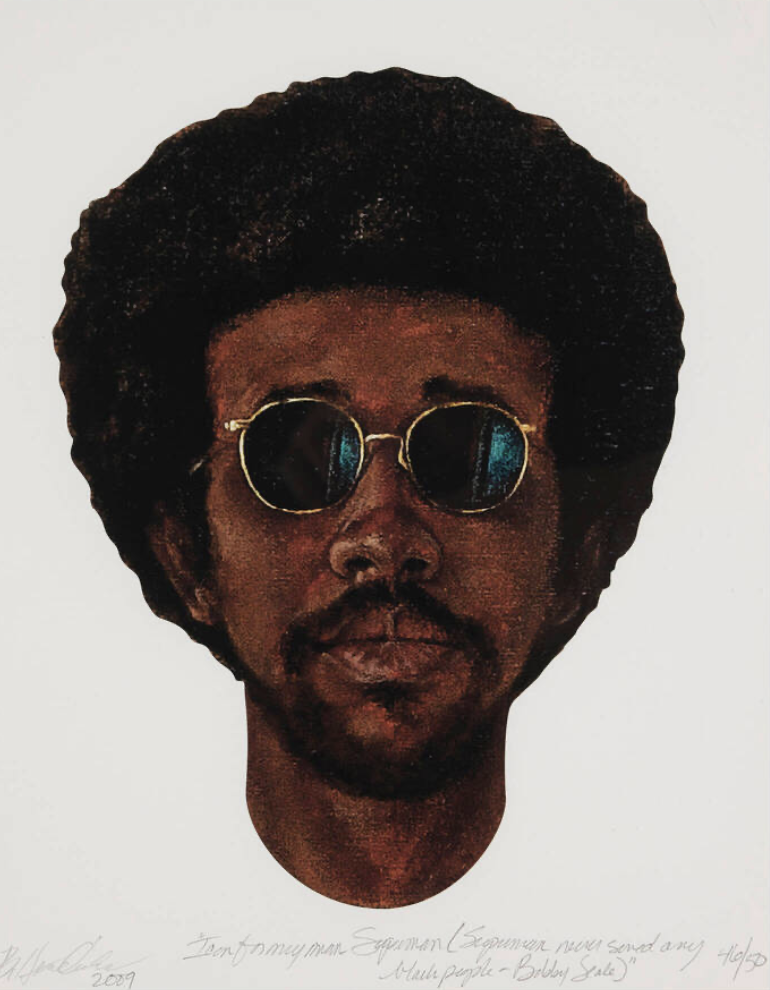

Hendricks' breakthrough came with works that merged historical painting techniques with contemporary Black identity. His 1969 self-portrait "Icon for My Man Superman (Superman Never Saved Any Black People—Bobby Seale)" exemplifies this revolutionary approach. In this painting, Hendricks depicts himself naked from the waist down, wearing a Superman shirt and sunglasses—a bold statement that challenged both superhero mythology and artistic convention.

The title references Black Panther co-founder Bobby Seale's famous critique of American heroism, but Hendricks transforms this political statement into something more complex. By painting himself as an icon—literally, with oil, acrylic, and aluminum leaf on linen canvas—he reclaims the visual language of both religious art and comic book culture.

Hendricks' portraits were produced mostly between the late 1960s and early 1980s, featuring cool, stylish, and self-aware Black subjects painted with vivid precision against radiating monochromatic backgrounds. These weren't political protests or victim narratives, but celebrations of Black identity, style, and presence.

Technical Mastery Meets Cultural Revolution

Hendricks demonstrated technical brilliance in his sensitivity to color and meticulously crafted style, capturing the nuances of darker skin tones and the textured articles of clothing that draped his statuesque figures. His work represented a critical precedent for a younger generation of artists, including Kehinde Wiley, Kerry James Marshall, and many more.

The influence of his "Icon for My Man Superman" continues to resonate. Artist Fahamu Pecou created "Nunna My Heros: After Barkley Hendricks' 'Icon for My Man Superman,' 1969" in 2011, explicitly paying homage to Hendricks: "It was truly one of the first experiences where I saw myself reflected, not just culturally, but in terms of my own visual aesthetics and approach to art."

Beyond the Canvas

In 1984, Hendricks turned away from painted portraiture during what he called the "Ronaissance"—the Reagan years—concentrating on landscape painting and photography for 18 years before returning to portraits in 2003. His comeback piece was a portrait of Nigerian Afrobeat legend Fela Kuti, demonstrating his continued engagement with Black cultural icons.

Hendricks taught at Connecticut College from 1972 until his retirement in 2010, influencing countless students while maintaining his artistic practice. His first major retrospective, "Birth of the Cool," organized by the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University in 2008, traveled to prestigious institutions including the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston.

Market Recognition and Legacy

The art market has increasingly recognized Hendricks' significance. Works like the 2009 print "Icon for My Man Superman (Superman never saved any black people - Bobby Seale)" now appear at major auction houses, with recent estimates ranging from $5,000-$7,000 for limited edition prints.

Hendricks died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 2017, just before a major Tate Modern exhibition opened. His death marked the end of an era, but his influence continues to grow. In early 2018, MassArt mounted "Legacy of the Cool: A Tribute to Barkley L. Hendricks," featuring 24 artists inspired by his work, including Amy Sherald, Hank Willis Thomas, and Toyin Ojih Odutola.

Hendricks once said, "My paintings were about the people that were part of my life." But in painting his community with the techniques and scale of the Old Masters, he created something far greater: a new visual language for Black identity that continues to influence artists decades later. In a world where Superman couldn't save Black people, Hendricks painted them as heroes instead.